In my REL 245 class, we’ve just started off the semester by watching Alfred Hitchcock’s classic 1959 film, “North By Northwest.”

In my REL 245 class, we’ve just started off the semester by watching Alfred Hitchcock’s classic 1959 film, “North By Northwest.”

Not seen it?

You ought’a.

We’re using it for a specific reason, of course: we’re examining the widely shared individualist assumptions that seem to guide much research on religion in the US (let alone research on religion elsewhere). That is, we’re taking as our object of study the fact that many scholars of American religion now seem to take for granted that we can call the landscape in the US a “religious marketplace,” one that it is best studied in terms of the reasons and results of various religious consumer’s individual criteria and personal choices.

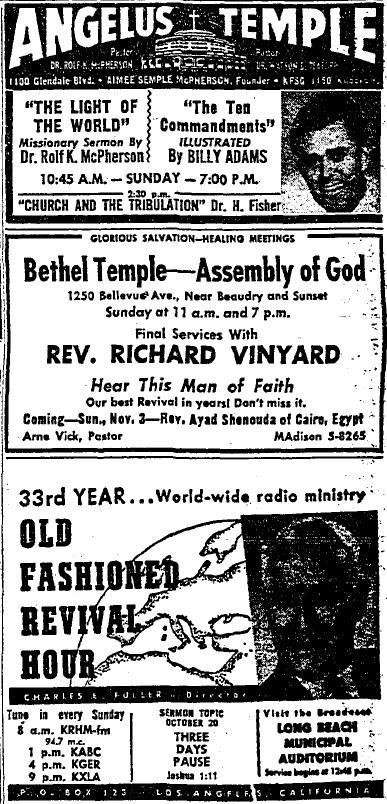

To rephrase: our starting point is to imagine someone coming to the US from elsewhere in the world — someone who might be intrigued by churches here advertising for followers (something we’d not expect to see elsewhere) — so as to ask why it is that we tend to think religion is so personal, and thus a matter of choices and preferences…?

To rephrase: our starting point is to imagine someone coming to the US from elsewhere in the world — someone who might be intrigued by churches here advertising for followers (something we’d not expect to see elsewhere) — so as to ask why it is that we tend to think religion is so personal, and thus a matter of choices and preferences…?

So, to start us off, we need to do some thinking about the notion of the individual that informs what, for some, is a now common approach (how ironic, of course, that this view on individualism is so widely shared and found in specific social sites, like here in the US for example…). For it may turn out that there’s nothing individual about feeling like an individual after all — if so, then the metaphor of shoppers in the religious marketplace isn’t nearly as helpful as some think.

So, to start us off, we need to do some thinking about the notion of the individual that informs what, for some, is a now common approach (how ironic, of course, that this view on individualism is so widely shared and found in specific social sites, like here in the US for example…). For it may turn out that there’s nothing individual about feeling like an individual after all — if so, then the metaphor of shoppers in the religious marketplace isn’t nearly as helpful as some think.

And that’s where Alfred Hitchcock in the first full week comes in.

For the film’s narrative gets going only when an advertising executive, Roger Thornhill (played by Cary Grant — the George Clooney of his day), who is at the club to have drinks with clients, is mistakenly identified as a mister George Kaplan.

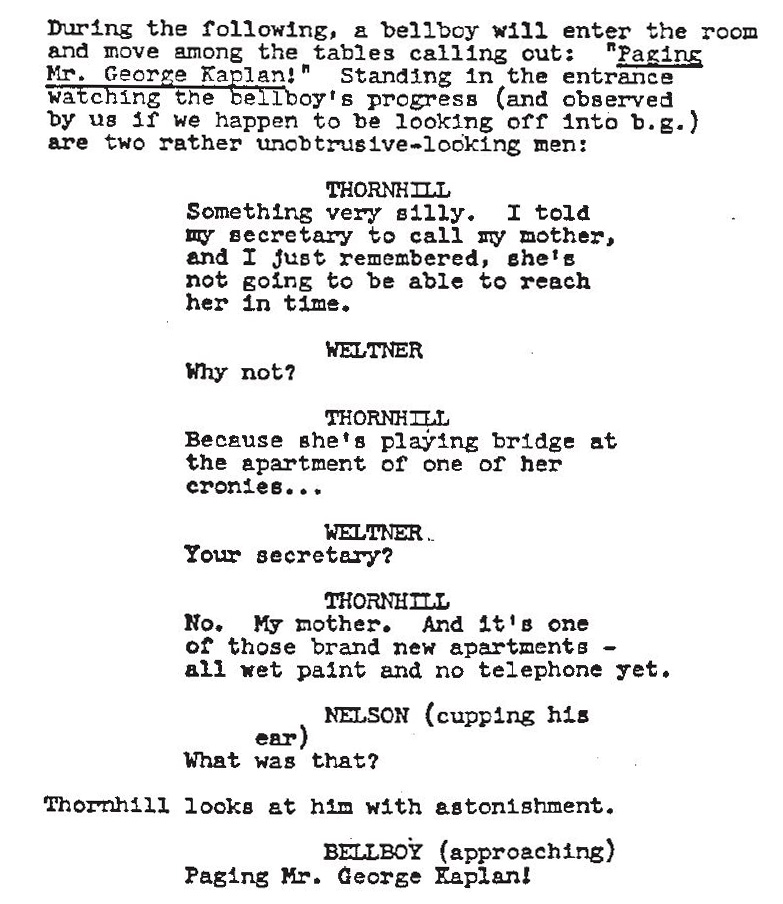

From the script we read:

Thornhill decides to sort out his mistake.

Thornhill decides to sort out his mistake.

Lurking in the background, waiting for Kaplan to identify himself, are two henchmen — who plan to whisk him away.

Lurking in the background, waiting for Kaplan to identify himself, are two henchmen — who plan to whisk him away.

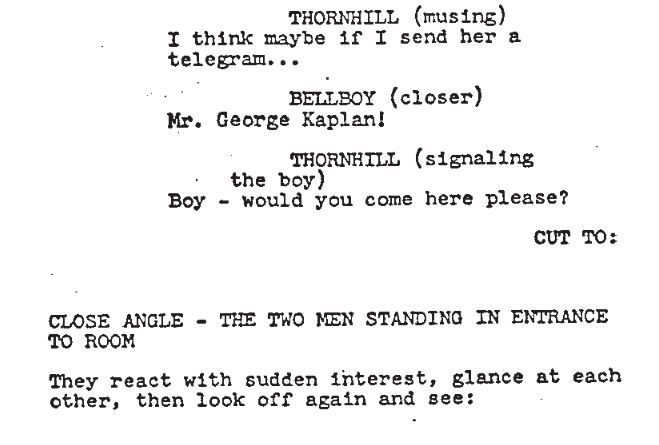

And they see Thornhill hail the bellboy, for purposes unknown to them, of course, and for reasons that have nothing to do with the page being announced for Kaplan.

Sure, we know they’ve mistakenly identified Thornhill, but they don’t — and, given that there’s no such thing in the real world as audiences who possess a detached, all-knowing narrator’s vantage point, the only one who knows is Thornhill himself. But since they assume he’s a government agent (am I giving too much away), they pay no attention to his repeated protestations…

Since he’s assumed to enjoy a party or two, even his mother doesn’t believe him the next morning when he’s been found driving drunk and then arrested — after narrowly escaping a late night fate intended for Kaplan.

But the really curious thing about the movie (at least for our purposes) is that, sooner or later, Roger Thornhill, advertising executive, actually becomes George Kaplan — that is, the more he’s treated like a crafty and daring secret agent, hot on the trail of traitorous spies, the more he becomes that very agent.

In fact, he takes on a variety of roles throughout the film; as phrased by the man who soon becomes his nemesis, Phillip Vandamm (played by James Mason):

First, you’re the outraged Madison Avenue man, who claims he’s been mistaken for someone else. Then, you play the fugitive, trying to clear his name of a crime he didn’t commit. Now you play the peevish lover, stung by jealousy and betrayal.

Did I mention he meets the mysterious Eve Kendall (played by Eva Marie Saint) on a train while he’s on the run after being accused of murdering a man at the UN in New York? And that she turns out to be Vandamm’s lover…?

So who is Thornhill, really? And does Kaplan even exist? Does Thornhill…?

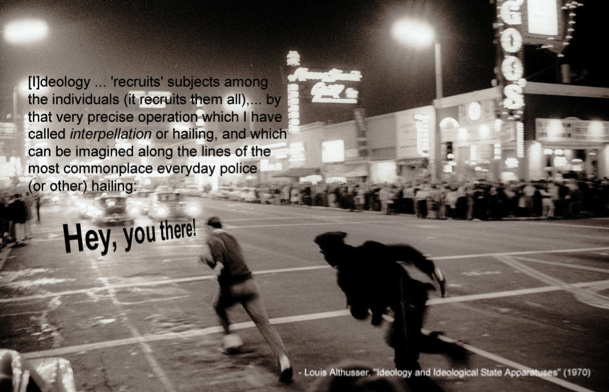

And this is exactly what Louis Althusser meant by interpellation. For it would be an error to think that we could reduce the Thornhill to any one of the many roles he plays throughout the film; for to Vandamm’s list we need to add, among others: precocious son, customer (he takes a cab ride, after all), the one Vandamm thinks he actually is all along, government agent, and not just two-time divorcé but, by the movie’s end, newlywed. The point? There’s no core beneath them all; although there may be a biological individual, that individual is repeatedly re-signified, called into existence, by means of the particular social interactions, with a collection of others, in each specific situation.

So place Roger in different settings and he becomes a different sort of subject — in his own eyes because of the eyes of others.

Sure, the film’s got nothing to do with religion in America and neither does it have anything to do with understanding religion as something one can shop for and choose. But it does have everything to do with helping us to think through the assumptions about individuals and social groups that we have to make in order to even talk like this about choice and about religion.

Sure, the film’s got nothing to do with religion in America and neither does it have anything to do with understanding religion as something one can shop for and choose. But it does have everything to do with helping us to think through the assumptions about individuals and social groups that we have to make in order to even talk like this about choice and about religion.

So yes, we started off our course watching “North By Northwest” — because, to be honest, if a class on religion in American is all about learning the names of denominations and the dates when this or that important thing happened, well, students might as well skip paying steep tuition and just read the Wikipedia article care of the free WiFi at a good coffee shop. But what they can’t get in this article or that textbook is a set of tools to unlock the truly curious thing that’s been hiding there all along: the way authors and readers arrange their worlds in order to understand them and move around within them.

So yes, we started off our course watching “North By Northwest” — because, to be honest, if a class on religion in American is all about learning the names of denominations and the dates when this or that important thing happened, well, students might as well skip paying steep tuition and just read the Wikipedia article care of the free WiFi at a good coffee shop. But what they can’t get in this article or that textbook is a set of tools to unlock the truly curious thing that’s been hiding there all along: the way authors and readers arrange their worlds in order to understand them and move around within them.

thanks Russ for great analysis of a great film. Zizek himself couldn’t have said it better! And how about individualism as a core American identity as witnessed in the closing chase scene on Mnt. Rushmore?

Too kind; thanks much. And yes, those busts carved into the mountain side could themselves be the interesting eg., esp. when they serve simply as a backdrop to a chase scene.