This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

An index of the complete series (updated as each

article is posted) can be found here.

The first of the thirteen bullet points that comprise the main part of the draft document reads as follows:

Should we follow Marx, then we’d make the relatively uncontroversial prediction that every institution contains contradictions that, if unaddressed, threaten its existence as a uniform whole. And here, in the opening item, I think that we see some evidence of this — correction, we do not see it for, as will all such contradictions, it is not identified and thus there is no need to manage it. For the document is completely silent on the fact that the AAR, by design, houses a number of members who are decidedly not free to research as they see fit and thus cannot honor what the document describes as the highest ideals of intellectual inquiry.

Should we follow Marx, then we’d make the relatively uncontroversial prediction that every institution contains contradictions that, if unaddressed, threaten its existence as a uniform whole. And here, in the opening item, I think that we see some evidence of this — correction, we do not see it for, as will all such contradictions, it is not identified and thus there is no need to manage it. For the document is completely silent on the fact that the AAR, by design, houses a number of members who are decidedly not free to research as they see fit and thus cannot honor what the document describes as the highest ideals of intellectual inquiry.

To illustrate: very early in my career, before landing a tenure-track job, I had one of those brief job interviews in a small curtained room at our annual conference. It was for a position teaching at a private Christian college in Rhode Island; among the final questions I was asked was whether, if I was hired, I would be willing to sign their school’s statement of faith. And, while asking the question, they slid a short document across the table, for me to read. Now, although I had fairly strong opinions even then about what the field was and was not, I also wanted a job, rather badly, so I recall quickly looking for language to which I could agree and that would, hopefully, provide sufficient interpretive wiggle room to carry out the sort of research I then hoped to do. As I remember it, I found some vague wording that I thought might work. It was over 20 years ago so I don’t really remember the document’s actual language or the specific school, just the episode itself and some of my prep, which included looking over a that tiny state; who knew that the moment would one day transform from an anecdote to a fieldwork experience? So I reported to the two men who were interviewing me that, yes, I could sign such a statement.

I didn’t get the job; in fact, I’m not sure I ever heard from them again.

Now that I look back on it, sitting on one side of that interview table, rather powerless and positionless, and the statement of faith in the hands of those on the other side, this episode constituted a moment in which the AAR’s big tent tried (unsuccessfully) to house what are, to all parties in that curtained room, not just different but mutually exclusive approaches to the study of religion. For work in the field I then hoped to join was, I assumed, to be carried out according to the widely adopted practices of the modern research university and the requirements of the human sciences (where, I’d argue, the term academic freedom makes some sense — but just some, mind you) whereas the other version of the field, one seemingly at home in the Academy (given that they were interviewing for new colleagues at that particular conference — though weeding out applicants with that statement), was designed so as not to disrupt the operations and orthodox assumptions of a denominationally-run school.

Now, let me be clear: I have no difficulty with such schools existing, students attending them, and faculty having careers within them. My issue is whether studying religion within institutions that require their faculty’s agreement with a statement of faith (the contravention of which can, or will, risk one’s employment) ought to be understood to constitute but one more branch of the academic study of religion’s supposedly rich methodological diversity. For including such constituencies strikes me as seriously undermining what the AAR means by academic freedom.

As I indicated in the previous post, I am not a supporter of the AAR’s “come one, come all” approach — an identity that is evident if we consult the organization’s mission statement, where we read as follows:

All disciplined reflections are welcomed… — so long as they’re freely inquiring and critical. Yet we all know that there are statements of faith out there that some colleagues must sign. (For instance, consider this current story.) So what constitutes free for the Academy? I have a hunch that faculty who apply for jobs in such schools and who willingly sign such documents, and have long, productive careers there, often feel they’re freely studying whatever it is they study — topics that, in some or many cases, just happen to coincide with the school’s orthodox doctrines. Or what about critical or disciplined? Aren’t they also interpretable along a continuum so wide as to contain contradictory options?

All disciplined reflections are welcomed… — so long as they’re freely inquiring and critical. Yet we all know that there are statements of faith out there that some colleagues must sign. (For instance, consider this current story.) So what constitutes free for the Academy? I have a hunch that faculty who apply for jobs in such schools and who willingly sign such documents, and have long, productive careers there, often feel they’re freely studying whatever it is they study — topics that, in some or many cases, just happen to coincide with the school’s orthodox doctrines. Or what about critical or disciplined? Aren’t they also interpretable along a continuum so wide as to contain contradictory options?

For me, these are technical terms and their meanings are not self-evident (consult here for a recent discussion on just what I think we ought to mean by “critique”) and the utility of the AAR’s document is, I maintain, premised on the committee’s clear articulation of the limits and applications of such terms. So I went looking elsewhere for assistance, although I found the AAR 2006 Statement on Academic Freedom and the Teaching of Religion (footnoted in the first bullet point, above) to be of little help, since it too failed to define terms and simply quotes what I read as an outright contradiction in the mission statement. In fact, it so emphasizes the importance of “shared scholarly norms” that it is easy to image that AAR members signing statements of faith that curtail the scholarly questions they can ask (thereby making themselves responsible to a host of non-academic bodies and criteria) were not on the minds of that committee’s members either.

Simply put, the norms aren’t nearly as widely shared as these documents seem to assume (i.e., assert).

But, come to think of it, failing to define such terms might be the strategic way that such documents manage the contradictions, for now we have set no limits and virtually anything that focuses on the topic of religion counts as a reflection on it and the big tent is preserved — by the way, note the use of that word “reflection” in the mission statement: our work is not an explanation of religion or analysis or study of it, not even an interpretation or understanding. Using one of those words would risk taking a stand that marginalizes the others. Instead, it is a reflection on it — that this undefined word, in common usage, overlaps with such others as mediation and contemplation while also implying a mirroring or reproduction, is strategically useful, of course, for now we implicitly address the existence of those members whose work might not be governed simply by “shared scholarly norms,” though doing so without ever actually identifying a group in our midst who cannot engage in what many of us would consider free inquiry.

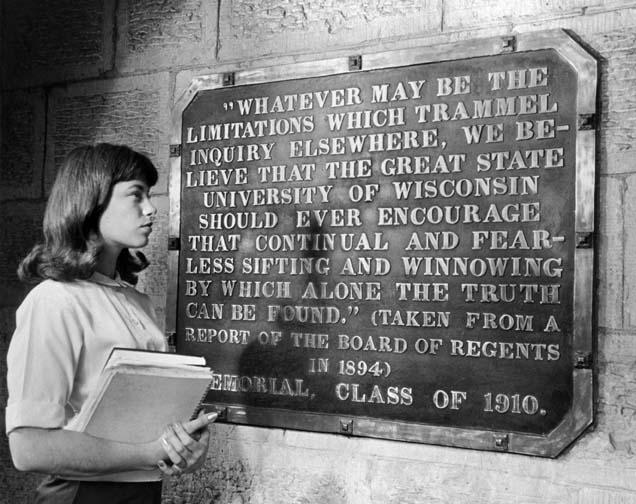

Side thought: might this unaddressed gap help to answer why, in its opening words, the first bullet point directs us to “honor” the academy’s highest ideals rather than, say, attain them? For with a contradiction such as this at the core of the organization, realizing these ideals is surely an impossibility for the academy as a whole — perhaps just as impossible as realizing the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s ideals (enshrined in that 1910 plaque, pictured above) given current Wisconsin state politics…

So what is the committee’s stand on all of this? Should this document address, head on, the lack of academic freedom for some members? (I’ve not even considered the practical conditions in which so many other members, all depending on their position in the academic hierarchy, feel they have to be mindful of what they study and teach — like the time [again, early in my career] when I was told by a senior colleague that I should remove the word “theory” and replace it with “approach” on a syllabus; or the time when I was called on the carpet and accused of unethical behavior because I shared a variety of course syllabi [all public documents, mind you] with grad students so they could get a feel for the many ways that an intro course could be taught; or the time….) Does defending academic freedom mean the AAR should work to eliminate such freedom-limiting statements of faith altogether or at least distance itself not just from the institutions that require them of their faculty but also the research that results when they are in force? If not, then what degrees of freedom exist and which are intolerable for our profession to thrive?

Or should we just continue to use undefined words like “freedom” and “critical,” much as politicians might use words like “hope” or “change”? For as long as everyone in the Academy has their own resonance with the term, they’ll probably use them as they each see fit and, more than likely, never attend each others sessions or sit across from each other at a job interview table.

And voila, the contradiction is managed because no one ever sees it.